A

t the 1901 and 1903 General Conference Sessions, the Seventh-day Adventist Church underwent a dramatic reorganization to ensure it could reach out to all the world.

Often, when we tell the story of the early twentieth-century reform of our church, we tell it as chiefly a story of administrative restructuring. But just as important, if not more so, was the mentality of the men elected as General Conference (GC) officers in 1901 and 1903.

Arthur Daniells served as president from 1901 to 1922; William Spicer served as GC secretary from 1903 to 1922 and then president until 1930. Both were visionaries of worldwide mission. Their joint passion, and that of the GC treasurers and vice-presidents who served alongside them and of the Secretariat team that Spicer gathered around him, was taking the Adventist message into unentered territories and to unreached peoples.

Their focus was what they called the mission field, which was vast as they defined it: all areas outside the Adventist homelands in North America, Central and Western Europe, and Australasia. The home fields were expected to take the message to the mission field. Spicer told the 1922 GC Session that elected him president, “The cause of worldwide missions is not something in addition to the regular work of the church. . . . To carry the one message of salvation to all peoples . . . is the aim of every conference, every church, every believer.”

Thus, to restructuring was added the collective passion of General Conference leaders to expand the boundaries of mission; together, these factors had a dramatic impact.

From 1901, the number of new church workers dispatched from the homelands to the mission field gradually increased up to the start of World War I (see figure 1). In 1913, the numbers sent out exceeded 150—triple the number sent in 1901. The number of new mission appointees plateaued during World War I but spiked in 1920 at 310, twice the number 10 years earlier. In all, in the first 20 years after the 1901 reforms, the Seventh-day Adventist Church sent out 2,257 new missionaries. One result was global expansion of the church.

In 1920, the North American membership was 51.7 percent of the total, and the rest of the world’s share was 48.3 percent; the corresponding figures in 1921 were 49.83 and 50.17 percent. Thus, 1921 was the year that membership beyond North America finally exceeded that within the North American Division (NAD). That was undoubtedly due largely to the number of missionaries and to the frontline, incarnational ministry that missionaries of that era performed.

While the figure of 300 new missionaries wasn’t matched again until after World War II, throughout the 1920s the number of new missionaries each year was more than 150.

There was a dramatic decline due to the Great Depression, with numbers falling below 100 per annum for three years. But for the rest of the 1930s, the church sent more than 100 new missionaries every year despite the severe financial constraints the church faced (see figure 1).

This number dropped again with the start of World War II, but even before the war ended, it was climbing, thanks to remarkably bold and visionary planning by GC president J. Lamar McElhany and secretary Ernest D. Dick in the darkest moments of the war. It is striking that, even in the 15 years from the start of the Great Depression until the end of World War II, there were 1,597 new missionary appointees.

The quarter-century following the war, 1946–1970, was the golden age of the Adventist Church’s foreign missionary program: in these 25 years, the number of workers sent to mission fields totaled 7,385. In 1969–1970, new missionaries totaled 970—by far the largest number of new missionaries sent into service in any two-year period in the church’s history.

But as figure 3 illustrates, it’s no coincidence that 1969–1970 marked the high point of the missionary enterprise, for 1970 concluded a quarter-century of steady growth in missionary numbers. The record number of missionaries sent overseas in 1969–1970 was a natural outgrowth of what came before: the high numbers sent abroad during 1945–1947, which were artificially inflated by the dispatch of large numbers of appointees who had been waiting for improvements in world conditions to travel. This inflation, in part, accounts for the apparent decline of 1948–1950, whose other cause was the collapse of the church in China. This was followed by occasional peaks and troughs in the 1950s and 1960s—yet overall, the trajectory was up, and, after 1950, sustainably so. The graph in figure 3 shows more than the annual numbers; it includes a fourth-order polynomial trendline, which shows more clearly the steadily upward trajectory in this era.

The rise of Adventist mission in the 25 years after World War II ended resulted from a huge, concerted team effort by church administrators, educators, medical leaders, and, of course, church members in North America, Europe, Southern Africa, and Australasia. But leadership was important.

The growth of the post-World War II years, like the dramatic expansion of the three decades after the 1901 reorganization, owed much to the GC officers’ commitment to mission. Reuben R. Figuhr, president from 1952 to 1966, and Robert H. Pierson, who succeeded him, had both served many years far from their American homeland as missionaries. Walter Beach, who served as GC secretary from 1954 to 1970, had also been a missionary, and he couldn’t have been clearer at the 1964 Annual Council when he declared, “We are a world missionary church—not just a church with missions in all the world.”

However, let’s go back to 1969 and 1970, which saw the highest and second-highest numbers of new appointees in our history: 473 and 470, respectively. These two years were the apogee. Since then, the story quantitatively, if not qualitatively, has been one of decline.

In sum, looking at the 120 years since the 1901 reorganization, from then onward, there was initially steady growth in the numbers of new appointees, checked only by the Great Depression and Second World War. This brief decline was followed by remarkable growth, which plateaued at the end of the 1960s. Since that point, the number of long-term missionaries appointed has gone steadily and inexorably down. Yet, this has happened while the membership is growing.

Figure 4 shows the ratio of missionary appointees per 10,000 church members from 1901 through 2019. The 1920s were good years, seen through the lens of the missionaries-per-10,000-members ratio, before the decline due to the Great Depression and World War II. Then, the chart shows spikes in the mid-to-late 1940s and the mid-1950s, reflecting the initial post-war mission expansion, sustained by rising church income in Western countries during the economically flourishing 1950s. But after 1970, there was a steep decline.

Furthermore, the nature of the work missionaries do has changed, and they aren’t as long-term as they used to be. Here are just a few examples of missionaries and their service.

George D. Keough and his wife Mary-Ann served as missionaries from Britain to the Middle East on three separate occasions, starting in 1908; their service in the region totaled 33 years, with another 4 years spent at the General Conference for a total of 37 years of missionary service. They began their third tour of duty when George was 65, an age when others would be retiring, and they returned to their homeland for the final time when George was 72.

George and Laura Appel went to the Far East in 1920 and spent the next 38 years in mission service—30 in China and elsewhere in the Far East, 8 in the Middle East.

Dick and Jo Hayden also spent 38 years as missionaries, working in the mountains and jungles of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador.

Merritt and Wilma Warren served in China and the Philippines for 47 years, starting in 1913, and didn’t return to their US homeland (which must have no longer seemed like a home) until Merritt was 69 and Wilma 72.

Ezra and Inez Longway spent 55 years as missionaries: 30 in the China Division and 25 in the Far East Division.

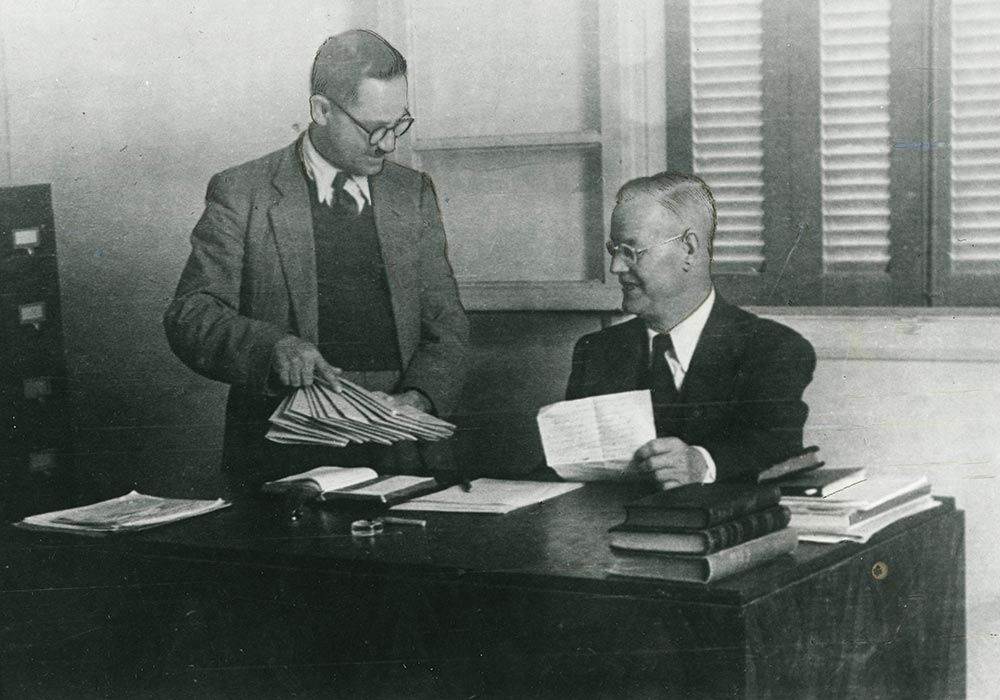

Keough, Appel, Warren, and Longway all had spells as union presidents, while Appel was Middle East Division president and Longway and Keough were division department directors. But all spent many years working first in frontline mission. Picture 4 shows George Keough sitting behind a desk in Lebanon when in his 70s, but during his first 21 years as a missionary he and his family often worked deep in the Egyptian hinterland where George would go and sit on the earthen floors of the local people’s homes, eating whatever food they gave him and winning them to Christ by representing Christ to them.

In contrast, today’s missionaries tend to be based in institutions and administrative headquarters. Of course, there’s a need for skilled medical practitioners, accountants, and IT professionals to serve the world church; but there’s also still a need for people today called from all around the world and sent all around the world to represent Christ to people who don’t know Him. The GC Secretariat’s recognition of this fact has led us to propose what is known as Mission Refocus, which includes allocating more missionary budgets to frontline mission work.